The outcomes will be shown in due course.

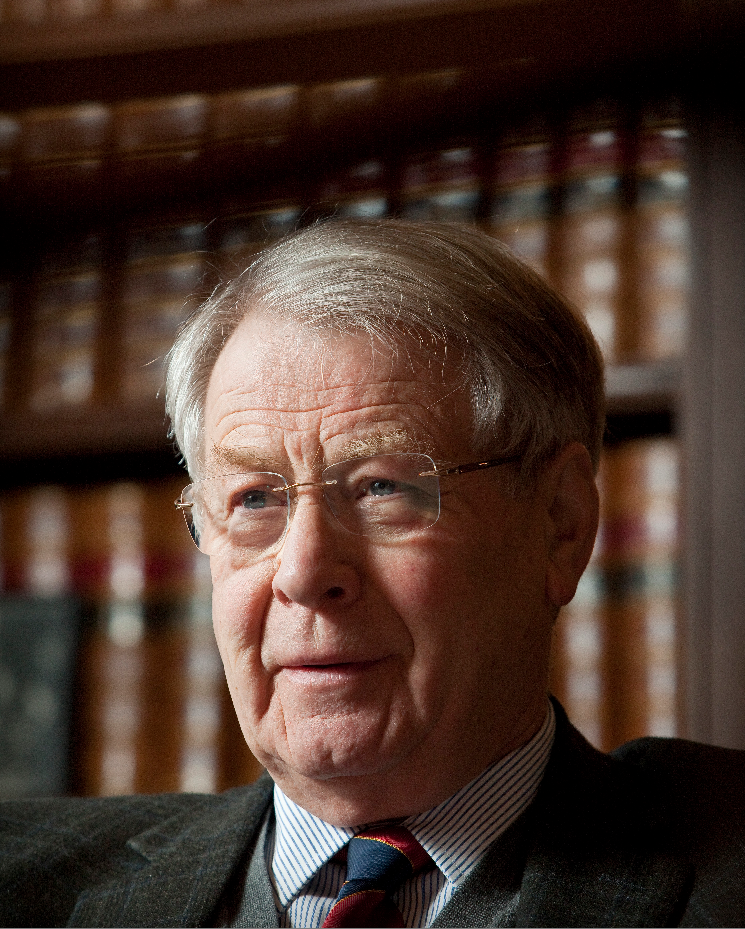

I have a specific affection for this instance, which I contended for the appellants. In these days, in the couple of weeks before Parliament declared in November, the law lords was able to sit at the room to demonstrate their proceedings were really proceeding of Parliament. They sat at small desks at the well of the room. Senior counsel in full-bottomed wigs dealt with them by a rostrum a couple feet so it had been like peering down into a fishbowl. There was space in the front of the rostrum for just the 2 leaders, using a little ledge for publications or newspapers. Juniors and attorneys sat a few feet behind. Peers, such as bishops in robes, wandered in and outside to listen to what was happening. It was an adventure that nobody is going to have again, now that what’s completed in mufti from the Middlesex Guildhall.

The actual problem in Brown has been that the character and extent of the powers of the Scottish courts to review administrative functions. The remedies available were slow and clumsy through activities of declarator and/or loss. Such activities could be increased in the Sheriff Court in Addition to the Court of Session. The question was if, however the Court of Session alone had power to review acts of public bodies (at Brown, the’act’ was conclusion of the District Council which Mr Brown was’intentionally homeless’). The Second Section, on a literal reading of Lord President Inglis at Forbes v Underwood (1886) 13 R.465, held that, because the council’s conclusion wasn’t’judicial’ in personality, the Court of Session didn’t possess privative authority, so the situation could move from the Sheriff Court.

The concept that the power of judicial review depended upon the character of this decision — whether or not it had been’judicial’ or’quasi-judicial’ — had contributed to a lot of intricate distinctions in law, although it maybe not to a fantastic extent in Scotland. Our job was to show, first, that judicial review (in the contemporary sense) was, by its own nature, a jurisdiction that could belong solely to the Court of Session; and next, that judicial review has been concerned with the appropriate exercise of forces, whether judicial, quasi-judicial or administrative.

My junior, Matthew Clarke, and I spent several days looking for the institutional authors and instances at Morison’s Dictionary to obtain the origin of the power of judicial review, in order to demonstrate that it belonged only to the’pre-eminent jurisdiction’ of the Court of Session. When it arrived at the hearing, there was a definite thrill in demonstrating that the technical wisdom of our judges at the time of enlightenment, and also to found our debate on their easy and lucid statements of principle. At one stage, Lord Diplock commented that the phrases used were amazingly contemporary. Lord Fraser stated in his address that the simple principle where judicial review has been based was said in 1756″in terms that, so far as they proceed, would be absolutely appropriate for the current day”.

Since Lord Fraser pointedly discovered, what wasn’t appropriate to the current day was that the clumsiness and delay of the accessible process for judicial evaluation. I bade farewell for this particular chapter of my own life by serving on Lord Dunpark’s Working Party that invented the modern process.

in 2010.